Illustration by Justin Rakowski.

By John Higgins PEO IEW&S Public Affairs

Army Acquisition has been called many things. A team sport. A challenge. An opportunity to support the warfighter.

All of these can be true on any given day in Army Acquisition, with the primary goal of pacing the threat, or as said more bluntly like a mantra by Brig. Gen. Robert Collins, the Program Executive Officer for Intelligence Electronic Warfare & Sensors: “Pace the Treat.”

In order to do this Collins’ staff at Program Executive Office Intelligence, Electronic Warfare & Sensors are identifying critical areas in their policies, procedures and personnel that they can change completely, streamline for efficiency or create whole cloth.

This series will explore some of their tasks and implementations from the first steps in acquisition from “hatching” new products to meet the needs of the warfighter to when the product “leave the nest” and become part of sustainment.

Some of these targets were mandated at the highest levels of the acquisition, some were mandated through evaluating team requirements and capabilities and some were mandated by Collins himself.

This series will examine the hows and the whys of these changes, what they mean, and what they hope to accomplish.

Process to Product Part 3: OSA, Foundation of the Future Forces

You have a choice: you can either create your own future, or you can become the victim of a future that someone else creates for you. By seizing the transformation opportunities, you are seizing the opportunity to create your own future. —Vice Admiral (ret.) Arthur K. Cebrowski

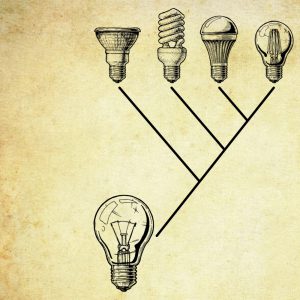

Thomas Edison did not invent the lightbulb.

The first experimental light bulbs were tested as early as 1802. In Edison’s time, at least 20 other people were developing lightbulbs with varying degrees of success.

Five years before Edison made his first long-lasting bulb, two Canadian scientists, Henry Woodward and Matthew Evans patented light bulbs filled with nitrogen. Irving Langmuir, who worked for General Electric, introduced the idea of filling the bulbs with a mixture of argon and nitrogen in 1908. In fact, filling glass with specific gasses would become the foundation for neon lights, invented by Georges Claude, first demonstrated in 1910.

But this article is very likely the first time you’ve seen those names.

Why do we only know Edison’s name today? Where did he succeed where others failed? First, gasses were not the solution, they were the problem: filaments in light bulbs will burn away any flammable gasses while inert gasses may not let the lighting element burn as bright or at all. Edison would be the first to create a true vacuum in the bulb before sealing his filaments inside, and this process was cheap and easy to reproduce. The other key innovation that would impact an entire industry, a nation and a culture was the Edison Screw, which was designed around finishing the vacuum sealing process while also creating a reliable electrical connection.

That familiar threaded connector that is now standard even if modern lightbulbs leave every other aspect of Edison’s invention behind. The year Edison filed his patent in 1880 he said “We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles.”

And since there are still candle based businesses to this day, it’s safe to say Edison succeeded.

Today, the Department of Defense is seeking to make its own “Edison Screw” – formally known in electrical engineering as an E26 base – for military software and hardware. The foundation across the branches is Modular Open Systems Approach or MOSA. In late 2015 the Army C5ISR center, the Air Force Lifecycle Management Center (AFLCMC), and the Navy PMA-209 came together and established the Sensor Open Systems Architecture or SOSA, an open consensus based standards body defining the key interfaces ala Edison’s E26 base for C5ISR and electronic warfare systems on military platforms.

Don’t Hope for it, Make it Happen

SOSA has incorporated inputs from multiple services, industry and academia. The Army contributed C5ISR [Command, Control, Computers, Communications, Cyber, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance] Modular Open Suite of Standards or CMOSS, which encompasses Modular Open Radio Frequency Architecture (MORA) and Vehicle Integration for C5ISR/EW Interoperability (VICTORY). SOSA also informs the Navy has contributed Hardware Open Systems Technologies or HOST and the Air Force adding Future Airborne Capability Environment (FACE) and still more letters to go into this acronym soup.

SOSA is the first serious, well supported by industry and government plan to have a common modular open systems approach across the U.S. Services, said Benjamin Peddicord, Chief, Intel Technology and Architecture Branch, C5ISR, Intelligence and Information Warfare Directorate (I2WD). “There have been a lot of programs that included open architecture, but SOSA bubbled up from the ground and is supported by industry and services in a newly robust way.”

“We’re aligning all those activities: Navy’s HOST, our CMOSS, the Air Force’s Open System Interconnection and FACE; they are all aligning under SOSA.” said Peddicord. “The Navy continues to use their HOST process for the same reason we maintain CMOSS, so we can all be quick and agile about our hardware and software.”

“I think our number one motivation when we started was tech insertion: be able to pace the threat and be able to field equipment and software that’s not obsolete to Soldiers. Probably a close second is reduction in size weight power and cost [SWAP-C], via hardware sharing,” said Peddicord.

“One of the main advantages to SOSA and CMOSS is rapid tech insertion,” said Jason Dirner, Electronics Engineer, C5ISR Center, Cyber/Offensive Operations Division. “It’s inevitable that when we get into a conflict we will identify a capability gap or a technology that we will need to get rapidly to the field. With how systems have been built in the past, ‘stove pipe systems,’ – proprietary systems that aren’t designed to work together – it would sometimes be too cost and schedule prohibitive to get that capability to field when the Soldier needs it and that needed to change. Using SOSA and using CMOSS establishing that modular open system approach exposes the key points in the architecture so you could rapidly integrate new capabilities, whether they’re hardware or whether they’re software in order to provide that capability to the war fighter when they need it. That’s the biggest value we see.”

This growing standardization across the board ensures that engineers, designers and builders of military hardware and software are creating within standard parameters.

“One of the concepts is that when you first see a certain platform and you have a new idea for something, you should be able to bring your application to that platform,” said Peddicord. “You should have a list of existing standards and access the existing resources on a platform whether they’re sensors, effectors or processors. You should have the foundation to be able to write an application that can consume information from a sensor, process that information and make a decisions for a cause and effect to happen.”

Ensuring these standardizations have the farthest reach is the mission of the SOSA Consortium, a diverse group of more than 70 different sponsor, principle and associate organizations between the DoD, industry and academia that have divided the various interests of all their stake holders into five specific categories: Architecture Working Group, Business Working Group, Electrical & Mechanical Working Group, Hardware Working Group and Software Working group. These five groups participate and develop products within their respective areas and with each other as needed. For example, the Hardware Working Group would work with the Software development group to develop a touch screen with some input from the Architecture Working Group during the development process to ensure overall compatibility.

SOSA, OSA and the Fight Tonight

Col. Kevin Finch, the Project Manager for Electronic Warfare and Cyber (PM EW&C) under Program Executive Office Intelligence Electronic Warfare and Sensors (PEO IEW&S), is leading the charge with how his products are being produced using CMOSS and SOSA requirements for his new development programs.

“We have too many ‘stovepipes of excellence’ and when that happens you have a lot of systems that individually function very well, but there’s not a lot of interoperability amongst those systems,” said Finch. “From that perspective, standards like CMOSS and SOSA, boiled down to the chassis perspective: it’s a standardization, a specific pin out, specific power capability output, around those needs my team created the EW&C architecture standard, informed by CMOSS.”

“So why SOSA? Immediately, I have the Multi-Function Electronic Warfare Air Large (MFEW Air), the Terrestrial Layer System (TLS) and the Cyber Warfare Battalion (CWB) Kit that we have to build out,” said Finch. “All three of these capabilities are going to be supporting the Battalion commander so with that in mind you have to look at how these technologies are going to be employed at the tactical level: together. The first priority is interoperability among those three systems, the MFEW Air Large, the TLS and CWB kit all have to first talk to each other and second, be able to process SIGINT [signal intelligence], EW and Cyber data. How integrate that first so they ‘play nice’ with each other, and second so they can easily ‘play nice’ with new systems that can be more smoothly integrated.”

Finch sees the SOSA Consortium, which his office is chief sponsor of, as key not just to his immediate implementation plans, but also critical to future plans.

The Consortium often employs “use cases,” which is how any software developer sees what different levels of users need and use a piece of software for.

An example of a use case would be analysis like this: the casual user might not need a lot of functionality, in say a search engine. The casual user types something into the search engine, they get a result they need and they are done. However, the business user might need not just one result, but what other results could come up, and they will need a means to access that information. The professional analyst user may need more information still, the results that come up, the results that get clicked on and perhaps the amount of time spent on a certain website.

The SOSA Consortium can ensure that use cases are shared with as broad a group as possible to see how different military users at different levels are using software and where that may be improved, and perhaps just as critically, what needs to be preserved or even replicated in other parts of a program.

“I’m the first PM that has mandated the use of CMOSS into one of their program of record systems,” said Finch. “I don’t expect it to be a totally smooth process but I do expect as we get a couple of sets and reps – to borrow from weight lifting – utilizing CMOSS and having a forum that is going to prove to be a very powerful development mechanism for us.”

“Yes, we have a standard now, but how can that change and how can we be ready?” asked Finch. “Is that the right format to use 15 years from now? It could be as simple as a midterm refresh, change the core chassis and slots, but it may be a software change. The consortium provides that mechanism to have that collaboration with industry and it prevents decisions from being made in vacuum, we’re making those decisions with the 60 plus companies that are affiliated with it.”

Finch and his efforts are aided by people like Dr. Adam Schofield, Senior Scientific Technical Manager (SSTM), Command Power and Integration Directorate, U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command (CCDC). Schofield’s job is to engage with project managers to ensure that needs are met, that system integration protocol is followed, and to ensure that these processes happen more efficiently.

“’Continuous modernization,’” Schofield began, “it’s a phrase I’ve heard around Army Futures Command. The commercial market place does that with computers: as new component technologies are coming out those get upgraded or incorporated into new products. Consumer grade computers are the best analogy because they’re full of standard interphases in both hardware and software. Connectors like USB, SATA [Serial Advanced Technology Attachment], P-SATA [Parallel-SATA], PCI-Express [Peripheral Component Interconnect Express], all those things allow me to add new processors and newer, faster memory. I can upgrade parts of my computer without having to rebuy everything. What we’re trying to do within Project Manager Position Navigation and Timing (PM PNT) and even more broadly for Electronic Warfare and Cyber is to mimic those concepts, which would allow us to upgrade and incorporate a capability as it comes out.”

As an example, for PNT, Schofield and a team of engineers, Soldiers and scientists came up with Modular Independent GPS Independent Sensors or MoGIS , a PNT specific Open System Architecture. The reason for this is the very concept of Assured PNT relies on being able to cross reference other types of data in real time from other sensors to ensure that data from a GPS is correct.

“How SOSA helps us do that is it first defines interphases,” said Schofield. “It defined – from a hardware perspective – mounted vehicles having a standard called Open VPX. That standard gave us the chassis that could fit different ‘cards’ that did different things. SOSA goes further and standardizes the pin outs in the interphase which allows all those cards to be interoperable and connect to and take data from multiple sensors. If I have an EW card that conforms to the SOSA standard, any back plain ‘slot’ that also conforms to the SOSA standard can take that card and use it. It really helps with the standard interphase and system messaging in both hardware and software.”

Open the Door For Outside The Box

Open System Architectures have the potential to be revolutionary, and there is one final component: having actual revolutionaries. To attract out-of-the-box-thinking and fresh talent in December of 2018, then Secretary of the Army Mark Esper approved a new Intellectual Property Management Policy for the Army. The Army’s old approach to IP was inconsistent and the Army would sometimes own too much of a piece of intellectual property and stifle its growth or own too little of it and would be left out of the largest improvements if it didn’t pay again.

“This is where that Edison thing comes in, even though Edison wasn’t thinking about LED lightbulbs, someone came along and made them. These standards are our version of the ‘E26’ light bulb base. The ability of someone who has a new novel way of dealing with a problem or a brand new problem presents itself,we now have a mechanism of integrating that new capability into the system with all speed,” said Finch.

“If you have some small third party vendor or a very niche company, the barriers to entry for that type of business are significantly reduced,” said Finch. “One of the problems I’ve heard as I have talked to a lot of the small companies: they’ll tell me ‘hey I have this intellectual property that will solve this problem you have, but it’s proprietary and these bigger companies don’t want to incorporate a capability that wasn’t even on the drawing board when they started their big project, and even if there’s a clear need we can’t get our foot in the door.’”

SOSA and programs like it open the door to smaller firms, first by giving them parameters that used to be only shared with larger corporations and second, following the new IP mandate, the Army will work with smaller firms to ensure fair compensation and sharing between the Army and their smaller partners.

“With smaller companies, we’re going to pay them for their intellectual property,” said Finch. “When we no longer need that particular IP and we unplug it and if that company wants to use it again we can just say ‘knock yourself out.’ That way companies can know their IP is being protected, but not completely absorbed by the military.”

Continuing Excelsior

If Edison and other people who were trying to create the final lightbulb we know today had instead worked together instead of competing, first establishing the E26 base and moving forward from there, light as we know it today would be very different.

Open Systems Architectures are creating common languages and standards across the branches, ensuring smoother communication, data and equipment sharing. As each branch finds more and more common ground through groups like the SOSA Consortium, equipment can be prototyped, tested and fielded much faster.

When military, government and business have come together to fulfill a certain need, it has resulted in truly amazing strides forward. The National Science Foundation (NSF) initially funded something called a Computer Science Network (CSNET) under the directive of The Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) of the United States Department of Defense. That would become ARPANET, and today, were refer to it as the internet. Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the Internet Protocol (IP), or TCP/IP, was established in those early years as a standard and it still used to this day.

Open Systems Architectures are primed to establish new standards that, like the foundations of the internet, can bring about revolutionary change.